Grandpa Abe and the Workers

By Chris Horst

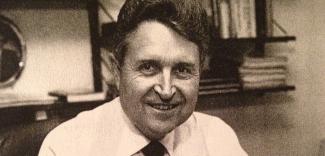

I sat on the countertop as my mom shared the tragic news: My grandpa—Abe Horst—had died.

A heart attack seized his last breath at the early age of 63. While reading the newspaper during a summer day in 1997, he passed. He was healthy and active and we were not ready to say goodbye. While our relationship revolved around my early adolescent affinities like pizza and beach vacations, I cherished him immensely.

I have learned more about Abe in retrospect. And the more I uncover, the more I mourn. Candidly, the pain of losing him is stronger today than it was then. I’ve learned Grandpa was an entrepreneurial risk-taker and a gifted manager. I’ve discovered he grew his real estate development company from 25 employees to over 600. I’ve visited his expert craftsmanship displayed in the buildings he constructed across the Susquehanna Valley.

In an interview on his leadership approach, Grandpa shared a value he held dearly.

“Our people are a joy and a blessing. Absolutely, I would say that is where our success begins. These are not just warm bodies. They are tradesmen and craftsmen who can work with their hands. They can visualize, see the picture of a finished job in their mind’s eye long before it’s completed. They’re proud of the work that they do and that shows in the work they do.”

From the farm fields to construction sites to executive suites, Abe demonstrated a truth he believed: God created us to create. And he let his workers know it. At his memorial service, hundreds of past and present employees lined up out the doors to share their respects. The volume of compliments we received from these workers astonished us. I’ve learned my grandpa was known for creating abundant time—even when he was the CEO—to visit his workers and sincerely affirm their abilities.

Work isn’t popular. It’s our cultural scapegoat, vilified for many reasons. Most-recently, Tim Kreider, a writer for The New York Times, penned a mostly thoughtful column on busyness, but lamented a widely held falsity: “The Puritans turned work into a virtue, evidently forgetting that God invented it as a punishment.”

When we examine our culture’s caricatures of work, it sure seems like work is cursed. We suffer through the “daily grind” because we’re “working for the weekend.” After all, “it’s five o’clock somewhere.” In our Office Space culture where companies like Dunder Mifflin are normalized, it’s easy to believe work is inherently flawed. In God’s design, though, people weren’t strumming harps on angelic clouds. The Garden of Eden wasn’t a Sandals Resort. In Eden, we see Adam and Eve meaningfully employed to tend their property. The first action God took and command he gave was to work.

Nearly all the biblical heroes of the faith practiced a philosophy of vocation that was redemptive, not resentful. Joseph’s career began in the sheep pastures and ended in the Egyptian Oval Office. Lydia designed clothing. Jesus knew his way around a woodshop. Throughout scripture, we see workers modeling creativity, diligence and purpose.

My grandfather understood this and instilled it in those around him. When Christians allow cultural stereotypes to become our narrative, we ask the wrong questions: How long till Friday? Why can’t every day be a vacation day? In a stirring Labor Day editorial, Rev. Bill Haley suggests we consider work differently: “How is my job creating good in the world?” or “How is my job helping fix what is broken in the world?”

Kreider suggests work is cursed so we should do less of it. Grandpa believed work is challenging and it’s good for us. Work isn’t an evil to be escaped. My friends who are unemployed, underemployed, or retired-without-purpose all attest: It’s miserable.

Work is cursed only when we relegate it to its stereotypes. Hundreds of workers came to Abe’s funeral not because he gave generous vacation time, but because my grandfather understood that God intended work as a gift to embrace, not a curse to escape.

Originally published at smorgasblurb

- Log in to post comments